Although the single-lap joints are more commonly used in composite material components, there several others approaches. Even though they look quite different, it is observed that they behave very similar with respect to single-lap joints. This article proposes a brief summary of the other types of junction for adhesives and bonds used in composite material parts and structures.

Double-lap joint

The double-lap joint behaviour in terms of shear and peel stresses is better than the single one, even considering the stress concentration at the edges. For double-lap joints, in some cases, the thermal stresses should be considered. For instance, when joining aluminum to CFRP, it is necessary to deal with a large difference on the thermal expansion coefficient. For the aluminum, the value is about 23.4•10-6 °C-1. This means that, when those materials are cured together, the aluminum tend to cure faster. However, to avoid this, it is cured with the interposition of an adhesive film and the carbon fiber.

Then it should be accounted that, at the cooling process, these materials will suffer a different contraction. Hence, for sure, shear stresses at the interface will be generated. These are represented in the Figure 2 by the cross-lines and they will sum-up with the mechanical stresses when the joint is pulled. This means that, if there are thermal stresses inside, then the final stress distribution which may be not symmetric, but it will be biased to one side. Then at this side (Figure 2) the structural shear stresses and the thermal shear stresses will sum-up. This can be avoided by performing the stresses relaxation step after cooling down.

Composite adherents

The adherents must be calculated considering that, the shear modulus is much lower than the elastic one. This is peculiar characeristic of the composite material. In the case of metals, this difference is much smaller, thus it is common to assume that those stresses are equal. In composite materials it is assumed that, the longitudinal deformation of the adherent is uniform at the thickness direction and the transversal shear stress in the adherent is linear along the thickness direction. Therefore, it is necessary to correct the shear stress modulus in order to account those aspects. This is done by dividing Ga by a coefficient Ksh, that accounts the properties of the adherents and adhesives.

Scarf/Bevelled joints

Scarf and bevelled joints are, theoretically, very good. If obeyed the conditions of equal adherents, t/L ratio about 1/10 and no steps at the scarf ends, they deliver the maximum performance of the joint. However, to design and machine a perfect sharp corner of a scarf joint is very difficult and expensive. For this reason, this configuration is usually referred as the ideal condition. One possible solution is the ply drop-off, which is a method to obtain a behavior similar to scarf joints. However, the result is not a perfect reproduction of a scarf joint. The main objective of this kind of joint is to obtain a balanced connection with respect to stiffness. This is defined by the thickness and Young’s modulus of the adherents. If one of them increases in thickness with respect to the other, the elastic modulus must be reduced in order to compensate this difference. If this was not done, the stiffness distribution along the connection would no be unbalanced. Hence, stress concentrations will arise. The the shear modulus equals to the average one.

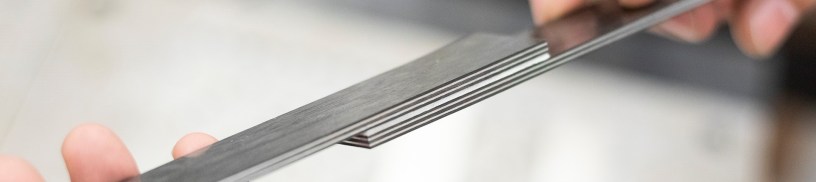

Doubler joint

A double joint is used to reinforce a structure by attaching another plater over the principal one. This second plate is called, doubler. It works similarly to a double shear configuration. Hence, the objective is to reduce the shear efforts on the principal plate. The doubler is able to divide the load on the principal plate, reducing it by the half of the initial value. Even though the maximum stress occurs at only one extremity of the adhesive, it reduces along its direction.

Cylindrical joints

Cylindrical joints are pretty much required in torsion and shear. However, its configuration and behavior are very similar to the single or double lap joints. Actually, in terms of shear stresses, the usual pattern is a very high stress at the extremities of the adhesive. It is possible to mitigate a significant part of these effects by tapering the adhesive at its extremities. The same pattern is exhibited for peel stresses, the high ones are in the extremities, while along the longitudinal length of the adhesive, the stresses are very low or zero.

Butt-joint

Another kind of joint is the butt one, it is commonly used for cylindrical parts joining. The main loads applied to it are tension and torsion ones. The problem of this kind of adhesive connection is that, the adhesive surface is at the same direction of the loads. This is a condition that should be avoided as much as possible. Usually, the adhesive has a different Poisson’s ratio with respect to the adherents. Actually this is pretty much the trend in composite materials, but for adhesives the difference in their modulus are significant. As a result, even though the joint is being loaded in tension, the deformations occur also at the axial, the radial and the circumferential directions. In other words, adherents and adhesive have a very different deformability. Therefore, the adhesive shrinks much more than the adherents. It tends to distort more near the extremities of the adhesive layer.

Peel joint

The peel joint exhibit a characteristic that, the peel stress has an oscillatory behaviour together with an exponential one. The maximum value is much concentrated at the peel point. This is tested because it is very demanding for the adhesive. Hence, it is possible to test very well if the connection is good, specially in the point of view of the adhesive. In addition, the test also separates the joint in two parts with a stress concentration in a point which is almost a sharp crack. Ideally, if this is more rigid than a sharp crack, there is a relationship between the peel load and the fracture toughness. Sometimes this can be estimated by peel loading.

References

- Adams, R.D. Comyn, J.W.C. Wake, Structural Adhesive Joints in Engineering. Edition 2, Chapman & Hall, 1997;

- MIL-HDBK-17-3F, Volume 3, Department of Defence (DoD) USA, 2002.