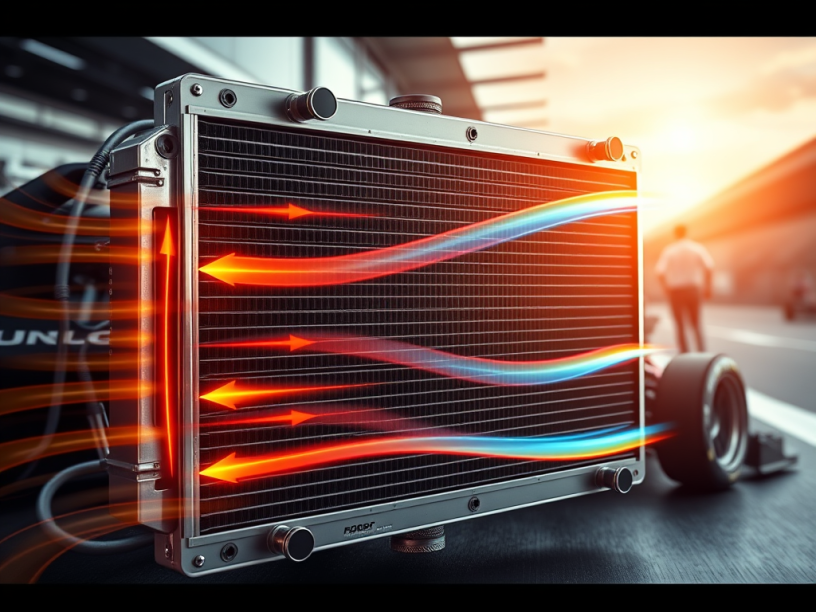

A physical radiator is modeled just in terms of macroscopic effects on the flow, which are the pressure and the heat rejection. The radiator model is a simplified one and the fluid crossing it creates a pressure jump and heat rejection. Usually, the radiator suppliers share the pressure versus velocity chart. As can be seen on Cover Figure, the pressure jump depends on the flow velocity across the radiator. The heat rejection is defined regarding the powertrain output. At first sight, the table at Figure 1 allows a second order interpolation function of the crossing velocity. Hence, the volume is characterized as porous media cells. In this case, it is applied the Darci’s law.

ΔP(v) = (μ∙v/α + ½∙ρ∙C2∙v²)Δn = a1∙v+ a2∙v²

The input parameters are:

(1/α , C2)

While a1 and a2 are given by:

a1 = μ∙Δn/α ; a2 = ½∙ρ∙C2∙Δn

Where C2 is the inertial resistance and 1/α is the viscous resistance. Hence, it is a quadratic function that delivers the pressure drop along the radiator. At this point it is given a table with the experimental data. When using a solver usually it is applied a porous media boundary layer. This means that the volume could be a sponge, which there is a flow running through all the surfaces. In the case of the radiator there is only one direction which the air can flow. Hence, CFD softwares ask to provide the 1/α and C2 quantities for each direction of the porous media, normally three. However, radiators have just one flow direction, while the others are walls. Hence, it usually adopts a procedure that, for wall it is set quantities with magnitude order three times higher, at least. In this way, the preferential direction is the one which is less resistant. This is a rule of thumb used in some car companies.

Exercise calculations

Considering a model that represent a radiator which have the following parameters:

- a1 = 66.81;

- a2 = 2.4;

- Δn = 58 mm.

The objective of this exercise is to calculate the viscous resistance 1/α and the inertial resistance C2. The procedure is described below:

a1 = μ∙Δn/α → 1/α = a1/(μ∙Δn) = 66.81/(1.75∙10-5∙58∙10-3) = 6.5∙107

a2 = ½∙ρ∙Δn∙C2 → C2 = 2∙a2/(ρ∙Δn) = 2∙2.4/(1.225∙58∙10-3) = 68

Hence, proposing another radiator sheet, it is possible to perform the same process. First, verify those data on a proper software for a labeled calculation, as Excel.

Then, plot these point in a graph of dispersion. Build the tendency line, the polynomial one since the Darcy’s law uses a polynomial equation. From this one it is found the coefficients a1 and a2. After that it is possible to 1/α and C2 applying the definition of a1 and a2.

a1 = μ∙Δn/α ; a2 = ½∙ρ∙C2∙Δn

Now, with a typical data from the radiator supplied already shown at Figure 1, it is possible to calculate the coefficients 1/α and C2 since the polynomial curve is calculated by the software.

As can be noticed by Figure 2, the polynomial equation is:

ΔP(v) = -8.3 + 26.8∙v+ 5.27∙v²

Hence, the terms a1 and a2 are given by 26.8 and 5.27, then the terms 1/α and C2 can be calculated as written below:

1/α = 26.8/(58∙10-3∙1.78∙10-5) = 2.595893065∙10-7

C2 = 2∙a2/(ρ∙Δn) = 2∙5.27/(1.225∙58∙10-3) = 148.3462350