There are several theoretical solutions for stresses in bonded joints, these were previously described. However, these are cases for simple geometries, which are single-lap, double-lap, scarf or cylindrical joints. Nevertheless, a racing car chassis has a complex shape, which their joints hardly are those ones. Therefore, in those cases, the best manner to understand where there are stress in the bondline, is applying finite elements. Its use is nothing different than making stress analysis in a component, except by the fact that, there are few details that have to be accounted for. The first one is that, the adhesive layer is much similar than the adherents ones in terms of order of magnitude. However, this results in a problem of mesh steering from the adherents to the adhesive. Since the stresses are concentrated at the corners of the adhesive, there is some mesh refinement in the corners. It is important to understand that, if the adhesive has sharp edges, the stress at these regions will be theoretically infinite.

Hence, as refined the mesh is, the higher will be the stresses found. For this reason there are simple techniques as round shapes and fillets in order to avoid such singularity (Figure 1). Figure 2 illustrates the solution for different types of planar joints, they always resembles the theoretical one in the value of the average shear. The exception is that the shear stresses tend to drop at the extremities, instead to drastically increase, because of the resolution of finite elements. These occurs in the last elements, because the stresses are not those ones which could be exactly predicted theoretically.

Mesh refinement

The mesh refinement is necessary in order to limit the number of elements just close to the corners. This can be done in planar joints, for instance. Another interesting refinement is the one regarding the elements on the adhesive layer. Usually, along its thickness it is suggested, at least, two elements in order to have an intermediate node in the thickness. Figure 3 illustrates an example with four elements. If it is used a quadratic element, then it is generated big size loads in comparison of having a single element in the joint.

Figure 4 illustrates another example of mesh refinement, which is done in two regions. In this case, there is one adherent and a filler of adhesive joint. The two regions of stress concentrations are close to the adherent extremity and at the structure near to the adhesive corner. The mesh refinement must be done following some rules. One is the aspect ratio, because the finite element must not be too elongated. The skewness is the angle in which the element is deformed. It is like a shear, but without any loading, instead is distorted due to the shape. There is a range of angles that this is acceptable (Figure 4). The third rule is the notch tapering, which is a ratio between the element sides limited by an angle with the horizontal.

Geometric non-linearity

The geometric non-linearity regards the case which, the finite displacement analysis is used to account the joint rotation. This may occurs due to the local bonding, specially in the single-lap joints. Figure 5 illustrates an example of the maximum normal and shear stresses using a linear or non-linear analysis. It is possible to notice that there is no significative difference, except in cases of a not so compliant adhesives. For instance, when using silicon or polyurethane ones. Another exception is the case which the adhesive must deal with different thermal expansion materials, like in solar panels. These are an adhesive compliant enough to deal with glass and aluminum thermal behaviours. These two exceptions are examples that might require the non-linear approach (Figure 5). In general applications, as structural joints, the geometrical non-linearities are not necessary to be evoked.

Examples

Figure 6 illustrates examples of stress distributions in the corner of a planar joint. It can be noticed that, there is always a concentration towards the sharp corner. The close form solution, seen in previous articles, takes into account the stress distribution across the thickness. Hence, there is one value and this is kept constant towards the adhesive layer. This is an assumption that, specially close to corners, there is a stress concentration.

The example in Figure 7 is the same situation as the previous one, but it is applied a small fillet at the corner of the adhesive. In this case, the stress distribution exhibits a significant reduction on the stress, there is no red area as seen in Figure 6.

If the fillet is further increased, that stress distributions will be even better. The maximum value seen in peel stress distribution is about 3 GPa, instead 17 GPa (Figure 8). The peel stresses are directly normal to the bond-line. They are much reduced when compared to a free sharp corners (Figure 6 and 7).

Elimination or reduction of the singularity

There are some solutions to eliminate sharp edges and the related stress singularity. These are corner rounding, tangential fillet and elastoplastic behaviour. They are basically the round of the shape of the edges. This is done with a round shaped espatula or tapered shaped one.

Mesh transition

In a situation which is necessary to separate mesh for the adherent and the adhesive, it is possible to model them as separate parts and join them through tight contact. This is a kind of kinematic constraint, which is used to attach different meshes. In this way it is possible to set the adhesive with a finer mesh, while keeping rather coarse mesh in the adherents. The last layer is composed by special elements, used for fracture simulations, these are the cohesive elements. They have a kind of behaviour which is different from the classic elements, in order to model the possible separation at the interface.

Elements for mesh complexity reduction

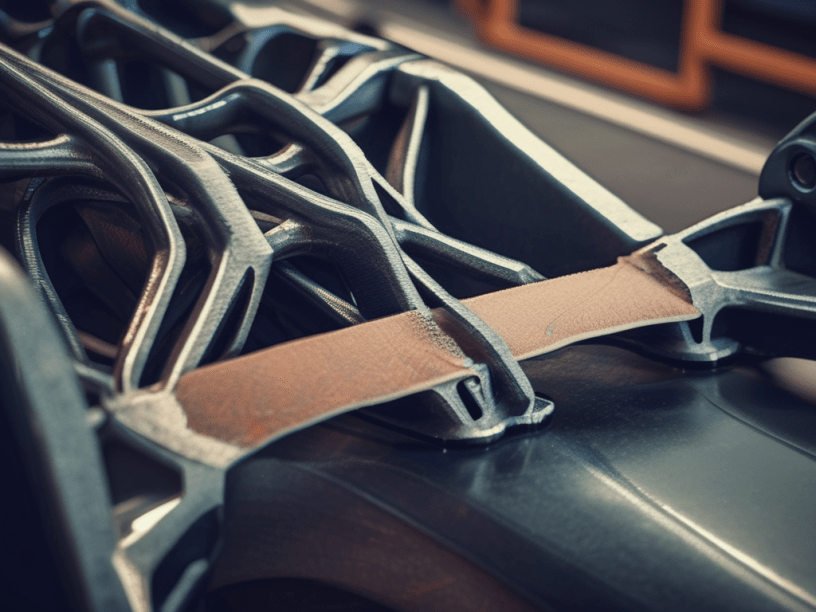

In cases which the parts are very complex, with different shapes or a large number of elements, it is possible to use other techniques. One of these is the substructuring, which has three approaches, the solid-shell transition and submodeling. The first one is based on modelling the bond as finite element, while the cylinder is made by shell elements. The submodeling approach is defined by shell model which its displacement is used as boundary conditions for a solid model. This is a way to get a detailed stress even though the model is very complex. Figure 11 illustrates an example of this technique applied to a wireframe chassis.

The tubes are converged into a structural nodes where they are adhesive bonded. Hence, it is done a first beam model of the whole chassis. Then, the beam model displacement, where it is used to model a mixed mesh of a structure, is used to feed the boundary condition of a local joint submodel. This process takes some time to be implemented, but it provides a very detailed stress distribution in the bonded region for each joint.

Mechanical properties to be introduced into the model

The main mechanical properties that should be introduced in the model are the elastic constants of the adherent and the adhesive. In the case of ductile adhesives, it is necessary to have the stress-strain behaviour or, at least, some significant parameters, like the yield stress, the ultimate stress and the failure strain. If the thermal behaviour is known, it is possible to have the temperature dependance of properties. This is important since polymers are temperature sensitive and the glass transition temperature (Tg) is fundamental for the manufacturing process. Those characteristics are tested by several standards.

- ASTM D638: Tensile test on bulk adhesives;

- ASTM D882: Tensile test on film adhesives;

- ASTM D1002: Shear by tension loading and metallic adherent;

- ASTM D5868: Shear by tension loading and FRP adherents.

Regarding the cure process, some adhesives can not be cured in bulk. Cianoacrylates are examples of these, they are hard to test for bulk properties. Other interesting properties to improve the finite element model are the coefficient of the thermal expansion and, maybe, the volume shrinkage. Another point that, in some cases it is necessary to be addressed, is the creep behaviour of the adhesive joint.

The reason is that, adhesives as polymers, are always prone to creep. This is a deformation that occurs under static loading. The creep is triggered by, either the temperature or the failure stress. Hence, if the temperatue is close to the glass transition temperature, the polymer adhesive will be prone to creep. Another condition is loading, if it is applied a load which is very close to the failure one, the adhesive will be prone to creep as well.

References

- Adams, R.D. Comyn, J.W.C. Wake, Structural Adhesive Joints in Engineering. Edition 2, Chapman & Hall, 1997;

- MIL-HDBK-17-3F, Volume 3, Department of Defence (DoD) USA, 2002.