The dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) is a test that is between the fiber and the matrix activation during the experiment. It is based on three standards, which are ASTM D5418, D4473 and D7028. Additionally, this kind of test is also a midpoint in between the mechanical and the thermal experiments. The first normally evaluates the definitive performance of the material regarding stress, strain, and elastic modulus. The thermal experiments are represented by the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), which defines the degree of cure of the specimen. Considering that composite materials are usually applied for components that operate under critical conditions regarding loading and environment, DMA is useful to check the material performance under temperature variations.

Dynamic mechanical analysis summary

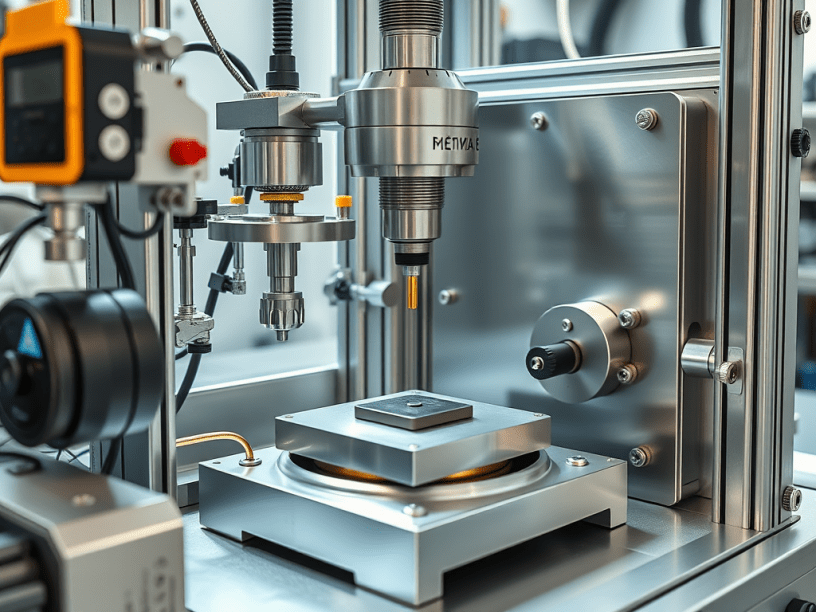

The DMA machine is a compact structure composed of fixtures, displacement measuring devices, electric motors, thermocouples, a furnace and a compressed air system. Basically, this machine applies an oscillating load on the sample in order to generate some fatigue and a displacement amplitude.

Thermomechanical characterization

The main objective of DMA is the material characterization with respect to its thermomechanics. The problem is that polymers are usually viscoelastic. Then, when the material is excited, there is a mismatch between the signal of the force and the one of the displacement. This occurs because there are elastic and viscous characteristics that reflect an ability to store and lose energy, respectively.

These can be modeled by the Hooke and Newton elements. The first defines the Hooke element, which is a spring with a known stiffness and displacement. Then, considering a material with a known elastic modulus and strain, it is possible to calculate the stress at this material.

If it is considered the Newton element, the principle is similar, but it is based on dashpot effects. This states that the material has a damping characteristic which is defined by a proper damping coefficient. Once this and the rate of strain are known, it is possible to calculate the stress.

Those elements act differently on the material. The Hooke one has an immediate effect once the material suffers a stress; thus, the phase angle δ is zero. When considering the Newtonian element, the response to the stress comes with some delay, which, considering a Newtonian liquid, the phase angle δ is about 90°. However, these are examples considering materials purely elastic or viscous.

Figure 5 illustrates the behavior for viscoelastic response. As can be seen, the response due to the stress does not come in an immediate way. There is a small delay or lag in the effect due to the stress. Hence, in polymers, the strain comes with some lag after the stress. The application of these concepts to the material characterization is developed by considering the forcing as a sinusoidal oscillation. Then, the stress can be written as

σ = σ0∙sinϖt

The stress variation along the experiment can be obtained by deriving the stress formula above:

σ'(t) = ϖ∙σ0∙cosϖt

Then, the strain can be calculated by

ε(t) = Eσ0∙sin(ϖt)

Composite materials work between a Hooke element and a Newton element. If the material is working near the Hooke limit, the lag is minimal; thus, the strain can be calculated by the following formula:

ε(t) = η∙σ0‘(t) = ϖ∙σ0∙cos(ϖt) = ϖ∙σ0∙sin(ϖt + π/2)

Hence, a real material can be described by an equation that calculates the strain as a function of the phase angle δ.

ε(t) = ε0∙sin(ϖt + δ) = ε0[sin(ϖt)∙cosδ + cos(ϖt)∙sinδ]

ε(t) = ε0∙sin(ϖt)∙cosδ + ε0∙cos(ϖt)∙sinδ

Inside this equation there are the terms that represent the store and the release energy, which are

E’ = ε0∙cosδ and E” = ε0∙sinδ

Then, the elastic modulus is given by the following equation:

E* = E’ + iE”

As can be seen, there is a real and an imaginary part of the material stiffness. Hence, when a sinusoidal loading is applied to the specimen, the stress and strain will vary sinusoidally. The sum of the components of the storing and releasing energy defines the elastic modulus of the composite.

Test mode

Basically, the dynamic mechanical test (DMA) can be performed in two approaches, the isothermal and the temperature-based ones.

Isothermal tests

The isothermal tests are subdivided into two categories: the creep and the stress relaxation tests. The creep test is based on the application of constant stress during a known time period. Hence, it is a measure of strain in function of time. Figure 6 illustrates the plots of a creep test applied to Hooke, Newton and viscoelastic elements. As can be seen, the curves are quite different in their response. Basically, the creep test is the application of a force and the deformation is observed. The Hooke element has no variation on the stress and strain. The Newton element has a linear increase of the strain even though the stress is constant. The viscoelastic element exhibits a non-linear strain development, then a non-linear decrease once the loading is removed. However, in this last case, the reduction of the strain decreases on time. Actually, this is called creep recovery, while the strain previously developed is called creep. Therefore, the creep variation is defined by the quotient between the strain variation and stress, which is called creep compliance.

The relaxation test is rather an opposite case with respect to the creep ones; it is based on the application of a constant strain to measure the stress variation as a function of time. This decrease is called relaxation, but it only is mentioned when describing the elastic modulus as relaxation modulus, which is seen in Figure 7 by G. Hence, once a constant strain is applied, the stress and the relation modulus decrease over time.

Temperature based tests

The dynamic mechanical analysis can also be performed under temperature variation. This kind of testing is based on a specimen under a constant amplitude of constant frequency excitation. The first case implies that the test will be performed with frequency variation of the stress and strain. On the other hand, the tests performed under constant frequency are based on a specimen exposed to variable stress and strain with respect to the amplitude.

Arrange

The test arrangement in which the dynamic mechanical analysis is performed has several variations. Figure 8 illustrates these, and each of them provides a different stimulus on the specimen in order to obtain different results. Hence, it is necessary to clear knowledge of what is the objective of the test. The 3-point bending arrangement (Figure 9) is used when it is being evaluated for very stiff composites. Additionally, this test is usually performed in conditions with reasonable temperature in order to hold the material below Tg. The single cantilever bending arrangement is used for the analysis of very stiff materials as metals and some composites. The objective is to determine the bending characteristics of the material that will be used in situations of heavy tensile stresses as bars. This arrangement is also adopted for measurement below Tg. The dual cantilever bending arrangement is adopted when the experiment is focusing on not so stiff materials. It usually uses thin samples. The tension arrangement is basically a tensile test made in small and thin specimens under a controlled environment. Similarly there is the compression arrangement, which is usually performed in foams. The shear arrangement is usually applied in elastomer and pressure-sensitive adhesive specimens. Additionally, this experiment can be a complement to DSC since it is possible to analyze some curing reactions.

Standards

There are two standards defining the test rules and procedures; these are ASTM D4473, D5418, and D7028. Between these, the last one defines the test procedure. Hence, this report follows its definitions, which state that the test is performed at a constant strain frequency of 1 Hz. Additionally, there is a temperature rate of 5 °C/min.

The most important statement of these standards is the glass transition temperature (Tg) definition. For that, it is necessary to plot the storage modulus, which is given by E’, against the temperature. Figure 10 illustrates an example. As can be seen, the procedure is basically the same as the one for differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Two lines are drawn on the curve, one is an extension of the constant straight section, while the other is an extension of the linear decrease of E’. Those lines cross each other somewhere in the graph. At the point where this happens, a vertical line is drawn until the temperature axis. Hence, it is registered as the glass transition temperature, Tg.

Specimens

The specimens are simple rectangular plates with dimensions according to the material used.

Test procedure

The test procedure can be summarized as follows:

- Connecting ducts of the compressed air;

- Assembling the clamps according to the type of test, for instance: three point bending;

- Configuring the machine software regarding the clamp calibration;

- Defining the test mode, for instance: multi-frequency strain;

- According to the standard, it is defined as a constant strain amplitude of 1 Hz and a temperature ramp of 5 °C/min from 35 °C up to 250 °C.

Subsequently, the test begins, and it is divided into three stages: the temperature equilibration, the loading, and the cooling. After the test, the calculations and their plots are built by the machine software. Hence, the procedure to draw the lines and to calculate Tg is done by the software.

References

- TA Instruments. Thermal Analysis Brochure. 2011;

- ASTM-D7028-07. Standard Test Method for Glass Transition Temperature (DMA Tg) of Polymer Matrix Composites by Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA). ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2015. DOI: 10.1520/D7028-07E01R15;